Nostalgia, Fun, and Programming

Published on 2021-01-05

Introduction

When we recognize music, movies, old photos, or video games of the past, it sometimes has a powerful effect: nostalgia. It’s a pattern of the past that we remember fondly.

When we write code, we also recall patterns of the past to consider as tools to help solve today’s problem.

I’d like to have some fun exploring the connection between software development and nostalgia.

What is Nostalgia

The word “nostalgia” started as a medical condition. Doctors invented the word with the Greek roots ‘nostos’, meaning returning home, and ‘algos’ meaning pain. It was invented in 1688, when Swiss soldiers would miss home so much, that they would mentally break down, and no longer be able to ‘be a soldier’; they longed for who they used to be.

The condition of ‘nostalgia’ evolved into much less than a medical condition, and more as a temporary emotion. The word is no longer associated with the negative effects to the person; in fact quite the opposite: it now means “fondly remembering the past”.

Inducing nostalgia can boost psychological well-being, increase feelings of self-esteem, social belonging, and encourage psychological growth. Nostalgia can be a restorative way of coping with negative stress.

Marketing knows about nostalgia; it’s a powerful selling tool. There are 11 Star Wars films; 10 Batman movies; 16 Final Fantasy games. Remasters of remasters, remakes on top of remakes. Remixes of older songs; you get it. Generally, folks want to be in that mental space.

Where Nostalgia Comes From

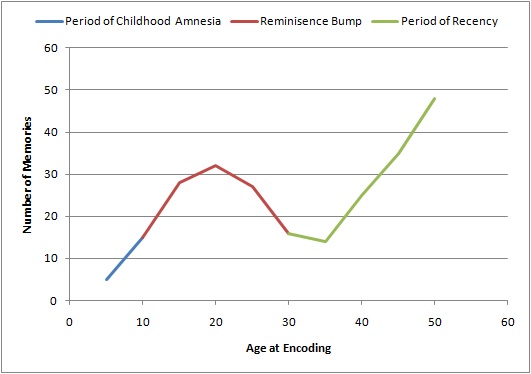

This is called the Lifespan Retrieval Curve.

- 0-5yrs Childhood Amnesia

- 10-30yrs Reminisence Bump (this is our nostalgic period)

- 30+ Period of Recency

Our autobiographical memory – that is, our psychological history of ourselves – on average shows that most of our memories are formed between the ages of 10-30 years old. Younger than 10 is considered childhood amnesia; greater than that is considered too recent. For the life of me, I can’t remember what being 6 was like. Likewise, I couldn’t tell you what I did 2 years ago that affected my life profoundly. It’s unconsciously regarded as too recent to be formative of “who I am.”

Our young adulthood is where we develop our self-identity; it’s when we discover who we are and want to be. We’ll come back around to that bit. For me, the time period is the 1990s and 2000s.

Back in the 1990s, there were several things that I did:

- Listened to cassettes I recorded from the stereo on my fuzzy earphones.

- Stopped at every Magic Eye book in Books-a-million, Borders, Hastings, or Barnes & Noble to see if I could see “it”.

- Spent 30 minutes or more just trying to decide what movie to rent; maybe it took so long because I couldn’t accept that the movie I wanted to see didn’t have the VHS behind it.

- Got really excited when the phone rang.

- Watched Bewitched and Dick Van Dyke on Nick-at-night.

- Replayed in my head the “The Log Song” from Ren & Stimpy. It was an earworm that never left. To this day I still hum it.

- I cleaned up poop from my Tamagotchi, jumped on goombas, and a little latter double-barrel shotgunned demons in Doom.

Let’s stop at that last point: video games.

Theory of Fun

Super Mario. The hero plumber that would grow up to be the most iconic and recognizable video game character of all time. Made by a company formed in 1889: Nintendo.

Video games are a source of nostalgia for many people. They’re fun. They’re a way to escape the stress of the day. Many video games, such as Final Fantasy, are epic stories that we can get lost within; just like books, but these are interactive! Others, like classic Mario, have very little story and just focus on addictive game mechanics.

Video games are developed to be fun; otherwise why would we play them? Most gamers aren’t playing for pure punishment (looking at you, Mega Man 9). Turns out, there’s a lot of social science that goes into designing games to get and keep players!

The book “Theory of Fun” outlines some basics of what it takes to create a good game. In it, the author Raph Koster includes a quote by Chris Crawford saying:

fun is the emotional response to learning

And later Raph Koster:

Fun in games arises out of mastery. It arises out of comprehension. It is the act of solving puzzles that makes games fun. With games, learning is the drug.

The idea was, games are systems built to help us learn patterns, and fun is a neurochemical reward to encourage us to keep trying.

These games are built to teach us patterns, and then delightfully introduce variations on them, which keeps us learning. We see new situations as the game progresses and have new ways to apply the learned patterns to them; or perhaps combine patterns.

Let’s look at an example.

In the original Super Mario Bros, we know that Mario moves right to advance to the goal; we can tell because he’s on the left side of the screen– you can’t go left; you must go right.

The game introduces a pattern by establishing if you touch the Goombas, you die. Noted– don’t touch bad guys.

Let’s try pushing one of the buttons on the gamepad. Turns out Mario can jump! Let’s avoid those bad guys. Noted– I can move right and jump

There are blocks now. Looks like if I jump into them, I might get something. If I jump on top, it acts as a platform.

It introduces a pattern by establishing if you touch the mushroom, you grow. Noted– there are power-ups that make me stronger

You experiment with two elements: Getting a mushroom, and then touching the enemy. Turns out that’s a mistake and now you shrink back down. Noted– can’t kill bad guys by only being big, and when I’m big and get hurt, I become small.

You experiment with two more elements: jump on the enemy’s heads!. Noted– bad guys can be jumped on.

Now we’re at a pit. Probably not safe to go in there, but maybe the screen will move down and reveal a new area. Let’s try. Noted– can’t go down pits.

These are universal patterns now in games. We know instinctively that we just don’t touch enemies, and we should jump over pits.

Patterns are Fun

Earlier we talked about nostalgia. Remember, nostalgia is fondly remembering the past. It’s remembering a pattern that may be long gone from our current life.

Like nostalgia, video games also has psychological benefits. “Theory of Fun” includes a study from 2011 released by East Carolina University, that found that casual gamers who played in 30 minute periods showed an 87% improvement in cognitive response time, reduced depression symptoms by 57%, and 215% increase in executive functioning. That’s incredible!

I’m starting to get the idea that nostalgia and video games are good news for our brains and well-being. This isn’t limited to video games either; although I’m focusing on them; these taught patterns also exist in music and movies.

Thinking about pop music, almost every song on the radio has a recognizable pattern, whether you’ve picked it out or not:

- Intro

- Verse 1

- Chorus

- Verse 2

- Chorus

- Bridge

- Chorus

- Outro

If we analyzed the musical notes, there are patterns of notes that musicians know sound good together called scales. Notes played that are not on the given scale will create a dissonant sound; an out-of-tune guitar, for example.

Likewise, movies and books typically follow a pattern:

- Introduce characters and setting

- Rising action or inciting incident.

- Climax and Falling

- Denouement (lessons learned)

Consider Tic-Tac-Toe; it’s definitely a game, but the pattern is easily perceived and there is no continuing variation. Mastery of Tie-Tac-Toe is quick.

Consider Korean dramas; usually a love story between a jerk guy and a shy girl. A series of events leads to the shy girl turning away from jerk guy, almost falling in love with another fella but then jerk guy gets hit by a car BAM now he has amnesia. This turns jerk guy into nice guy. Shy girl now likes nice guy. They get together, and then OH NOEES nice guy remembers stuff and now he’s a mostly-jerk-but-now-somehow-ok-guy. Seriously, every k-drama is this in a nutshell. Predictable.

Alas, there is a point where patterns become boring and no longer fun.

Delight tends to wear thin very quickly. Real fun comes from challenges that are always at the margin of our ability. When the balance is really perfect, people often zone out.

There has to be variance in the patterns to stay interesting. Games do this by having multiple stages or areas, power-ups, faster cars, etc. Music does this with different instruments, tempos, singers, etc. Movies does this new characters, settings, twists, etc.

Micro-lifecycles

We’ve explored nostalgia and patterns in popular media such as video games, movies, and music. What does this have to do with software development?

Generally, software development consists of applying code patterns to problems. Software developers, or really any artisans of their craft, notice and remember patterns. They remember which patterns work well and which don’t; what problems those solution-patterns are good fits for and terrible fits for. Software developers are players in the game of software.

People are amazing pattern-matchers. They look for patterns in everything; sometimes even finding patterns where there wasn’t supposed to be, like a cloud formation. In software, patterns that emerge are often collected into groups. At the macro-level, these patterns are called architectures, such as MVC (Model-View-Controller) common in backend frameworks, or MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel) common in frontend frameworks, or REST (Representational state transfer) common in web communication.

At the micro-level, it looks like spoilers a game. This micro-lifecycle is how every game works. Let’s look at the event loop of a game from the perspective of a gamer:

+----------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| All forms of feedback: |

| Art, animation, sound, music, movement, story. |

| |

+-------+-------------------------------------------^------+

| |

| A GAME ATOM |

| updates |

| +----+-----------+

| | |

+----v--------+ +---------------+ | 🔁 place |

| | | | input | |

| problem +----> preparation +------->+ +------------+ |

| | | | | | core | |

+-------------+ +---------------+ | | mechanic | |

| +------------+ |

| |

+----------------+Let’s change some of these words around and apply it to software development.

+----------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| All forms of feedback: |

| code review, performance, test suite, correctness, |

| those dang customers |

+-------+-------------------------------------------^------+

| |

| A SOFTWARE UNIT |

| updates |

| +----+-----------+

| | |

+----v--------+ +---------------+ | 🔁 test |

| | | | write | |

| problem +----> preparation +------->+ +------------+ |

| | | | code | | logic | |

+-------------+ +---------------+ | | | |

| +------------+ |

| |

+----------------+This looks like test-driven development!

- We’re presented a problem

- We prepare for a solution

- Have a test (place)

- Run the logic (core mechanic)

- And adjust according to the feedback we experience.

Software developers and gamers experience the same micro-lifecycles! But let’s call it what it is: it’s a rapid pattern.

Software development revolves around languages, architectures, and frameworks. These are all codified patterns with dissertations, white-papers, systems, and books written about them. Coders leverage these patterns to solve their problems faster.

Ruby on Rails is considered a really productive and fast framework for the Ruby language. It introduced the MVC architecture to a lot of young developers. Many developers of folks find Rails enjoyable; you have to follow the patterns that they set out to keep progress smooth. PHP Laravel is similar. There are dozens of frameworks that are aimed to be productive.

It wasn’t always like this though. Let’s talk about JavaScript.

Back in the early 2000s, the web looked entirely different. JavaScript, believe it or not, wasn’t as widely used as it is today. It was a mess; different browsers implemented different features, and sometimes the same feature but with different interfaces to it. There weren’t many patterns. It wasn’t as popular because it wasn’t as enjoyable to work within. Think of it as the wild wild west; only those willing to leave the comforts of what they knew and explore the unknown would be able to move the language and its ecosystem forward and help define it.

2006 came around and so did a little library called jQuery, which codified how to do basic actions in JavaScript. It standardized, unofficially, how to access elements on the page, how to handle events, how to animate. It was an amazing contribution to the JavaScript community. It’s still used today! jQuery inspired browser makers and some of those behaviors were codified into the language properly, and some of those APIs are integrated into the browsers now and work natively without the library.

Several years later in 2010, Google released a framework called Angular (known as AngularJS now). This was a full framework that applied the MVC and/or MVVM architecture to JavaScript.

Years later in 2013, another library called React was released. Together with other libraries like React Router, Redux and more, it essentially formed a new framework.

Shortly after in 2014, Vue was released, picking up some loved patterns from both Angular and React.

These islands of patterns are where developers congregated. Like little nation-states, they liked their leaders, disliked their leaders, stagnated, experienced rapid growth, poached employees, etc.

Together, the patterns that these libraries and frameworks introduced helped make frontend development much more enjoyable. JavaScript today is one of most prolific languages out there, no doubt in part because patterns emerged.

I think these patterns determine how much fun we’re going to have programming.

Elixir

Let’s talk about a software language called Elixir.

Elixir is a relatively new (born ~2011) functional language.

Elixir is a dynamic, functional language designed for building scalable and maintainable applications.

Elixir leverages the Erlang VM, known for running low-latency, distributed and fault-tolerant systems, while also being successfully used in web development, embedded software, data ingestion, and multimedia processing domains.

Elixir is beloved by developers, particularly seasoned developers, and I want to explore why. In fact, Elixir is the entire motivation for me to produce this content.

The Vault team [at Heroku] doing Elixir is only three engineers. Most of their apps are used internally, so they are generally not worried about performance. They continue using Elixir because they feel productive and happy with it. They have also found it is an easier language to maintain compared to their previous experiences.

– “PaaS with Elixir at Heroku”

What makes Elixir so enjoyable? As we have been exploring, fun is the emotional response to learning, and since people are amazing pattern-matchers, we constantly look for patterns. Perhaps Elixir has good patterns.

Let’s look at some common Elixir programming patterns. These patterns can be found in many other language. Maybe these patterns are why it’s enjoyable to develop in Elixir?

Pipelines

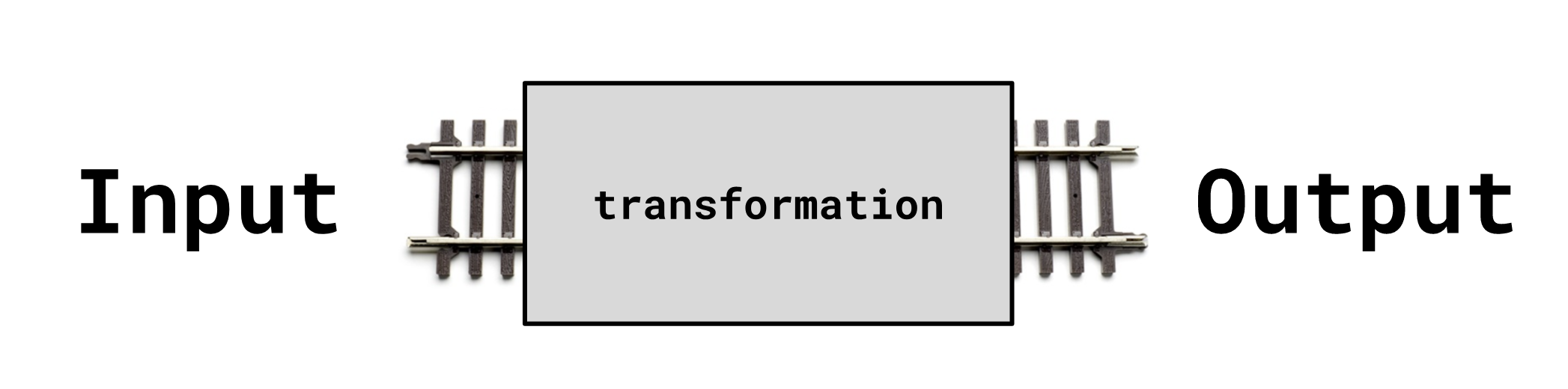

When we think about what an application accomplishes, we often frame it in our minds as a ruleset and transformation of data. That’s where we start, at least.

- Data comes in

- Data is transformed

- Data goes out

In Elixir, you can accomplish this with the pipeline operator:

"My String"

|> String.trim()

|> String.replace("My", "Your")

|> String.upcase()

#=> "YOUR STRING"

The pipeline starts with a string "My String" and passes it into the first

position of the next function String.trim/1. The result of that function is

then passed into the first position of the next function String.replace(..., "My", "Your") and so on until the end when we have the result "YOUR STRING".

Elixir developers reading this are probably already bored. We’ve seen this pattern a million times. But stick with me!

It doesn’t have to be all about transformation either. If at any point, we

wanted to see what the data was between any of those functions, we could also

throw in an IO.inspect() between the functions.

"My String"

|> String.trim()

|> IO.inspect(label: "the string is")

|> String.replace("My", "Your")

|> String.upcase()

#=> the string is: "My String"

#=> "YOUR STRING"

Move the IO.inspect down a little bit…

"My String"

|> String.trim()

|> String.replace("My", "Your")

|> IO.inspect(label: "the string is")

|> String.upcase()

#=> the string is: "Your String"

#=> "YOUR STRING"It’s a simple and effective way to see the state of your string as it’s passed through the pipeline.

The pipeline pattern is everywhere in Elixir, and it makes it clear how the data is being operated upon. We can see instantly that it’s being trimmed, we’re replacing a word, and upcasing the string. There’s no need to name interstitial stages of the string while it’s being operated upon. Opposed to this:

trimmed_string = String.trim("My String")

replaced_string = String.replace(trimmed_string, "My", "Your")

upcased_string = String.upcase(replaced_string)This is a simple example, but your eyes have to scan to the right to see the beginning of the data transformation, and then search for where that variable goes in the next function.

Pipelines are everywhere with Elixir.

The pipeline operator |> is not in every language, nor does it need to be in

order to write your code towards data transformation pipelines, but because the

operator exists, it steers developers to work in such a pattern.

Another form of a data pipeline is using the with macro. You may have noticed

in our simple example about that a string is passed in and out of all the

functions; there wasn’t a great way to check the output if it was successful;

with helps with that. Let’s look at that in our next pattern:

Monads

Ok, before I lose you, we’re not going to explore what monads are; it doesn’t matter. But, their effect is powerful and I want to explore a pattern that they enable. If you don’t know what a monad is, that’s totally fine. Here’s a simple definition: A monad is a unit of data and metadata (for the developer) about the data.

Not to say that Elixir has complete support for academic and mathematical monads like Haskell, but the Elixir community’s code style leans towards using monads, perhaps without even knowing it.

The best and smallest example I can think of for monads is the Result Monad:

case this_might_work() do

{:ok, success_data} ->

happy_path(success_data)

{:error, data_about_error} ->

unhappy_path(data_about_error)

end

In Elixir, we’re pattern-matching on the result of this_might_work(), and

that function returns a result monad. The monad in this case is a 2-item tuple.

The tuple begins with either :ok or :error which is metadata about the

accompanied data. {METADATA, DATA}

If the returned tuple’s first element is :ok, then bind the data to

success_data and move on. Likewise, if it’s :error, then bind the

unsuccessful data to data_about_error and move on.

This is a pervasive pattern in Elixir. I bet that 100% of Elixir codebases out there have this pattern in it. It’s extremely effective in how to route the data in the pipeline.

Here’s another one:

with {:ok, burger} <- McDonalds.order("burger"),

{:ok, fries} <- McDonalds.order("fries"),

{:ok, milkshake} <- McDonalds.order("milkshake") do

{:ok, [burger, fries, milkshake]}

else

{:error, error_message} ->

Emotions.frustrate()

Memory.remember(error_message)

{:error, "did not complete order"}

end

Look! We’re combining two patterns now: a pipeline and result monads. Here, we

are chaining several result monads together to form a pipeline with the help of

the with macro. Inside the with statement:

- order a burger. If you get a burger, then continue

- order some fries. If you get fries, then continue

- order a milkshake. If you get a milkshake, then you’re done! Grab your food and go!

If they don’t have one of the above items, then the pipeline will stop and return the first encountered error. SPOILERS the ice cream machine was broken, so we’re going to get an error when ordering a milkshake.

The result monad is extremely effective in crafting how to route data in pipelines.

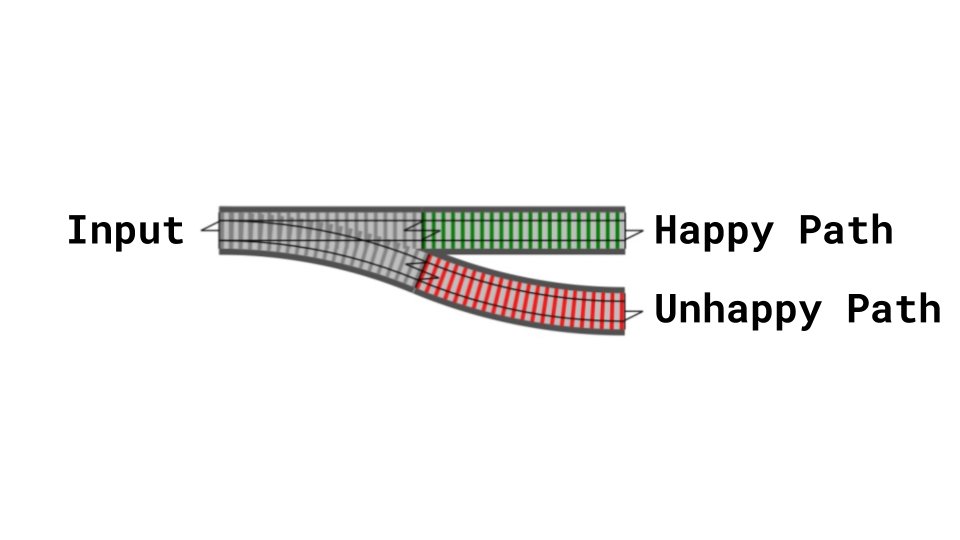

Happy Path

The previous example includes another pattern: seeing the happy path. I want to show you a couple of implementations of a process; one in Ruby and another in Elixir.

def order(params)

user = User.find(params["user_id"]) #| Happy path

return unless user #| Unhappy path

item = Warehouse.find(params) #| Happy path

return unless item #| Unhappy path

money = Billing.charge_user(user, item) #| Happy path

return unless money #| Unhappy path

schedule_delivery(user, item)

endIn this implementation, I can see that it needs a user, an in-stock item, and money charged before we schedule a delivery, but visually, I see a mixture of unhappy and happy paths. It’s a little difficult to quickly pick out what the desired outcomes are supposed to be. Again, this is a simple example; real-world code is harder than this in many cases.

Let’s try this in Elixir using the patterns we’ve identified earlier:

def order(params) do

with {:ok, user} <- User.find(params), #|\

{:ok, item} <- Warehouse.find(params), #| \ Happy Path

{:ok, _money} <- Billing.charge(user, item) do #| /

schedule_delivery(user, item) #|/

else #|\

{:error, _} -> nil #|_\ Unhappy Path

end

endHere I can see that the happy path is consolidated into one area. I know exactly what is expected for the process to complete successfully. I also know where the error cases are handled.

This code focuses on the solution first, which is important because for many many developers, the first goal is to make it work, then make it fast, then make it beautiful. With the solution consolidated at the top of the function, any readers know what makes it work and where to handle error cases.

Elixir isn’t perfect in this in all cases; it’s possible in any language to obfuscate a function’s happy path, but again the tool is here which helps visually organize the happy path.

Focusing on the solution is important; developers tend to think of what can go wrong and develop for those first. This leads to “gold-plating” your code before it often sees any real usage. More importantly, this way of thinking infects other areas of your psyche. It leads to anxiety!

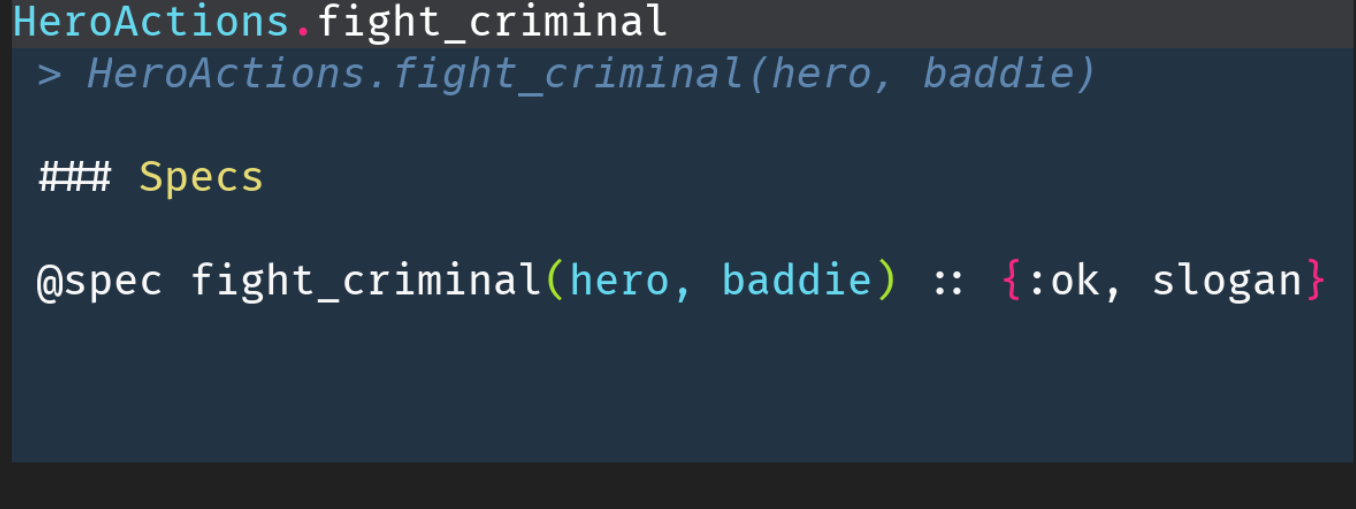

Totality

Total functions are functions that give you a valid return value for every combination of valid arguments. Total functions are really about communication. In Elixir, this is accomplished with a mixture of pattern matching and typespecs.

Elixir is NOT a statically-typed language, so it’s missing some tools here to ensure complete totality, but it does have tooling to help with communicating totality. Elixir can define types, and there’s a tool called Dialyzer that can integrate with your editor of choice that can provide hints to the developer. ElixirLS is one of those tools.

The pattern of totality in Elixir, in a sense, is simply good documentation. Developers annotate their code with docs and types to communicate to other developers what the expected input and output should be, and state guarantees on how it should work.

A basic example:

String.upcase expects an

input string and outputs a string. It will always succeed if you give it that

input, and will always return to you a string. It does not lie to you; it’s

total.

Here’s another example:

defmodule HeroAction do

@type hero :: WonderWoman.t() | Batman.t()

@type baddie :: GenericBaddie.t() | BigBoss.t()

@type slogan :: String.t()

@spec fight_criminal(hero(), baddie()) :: {:ok, slogan()}

def fight_criminal(%WonderWoman{} = hero, %GenericBaddie{} = baddie) do

%FightScene{

protagonist: hero,

antagonist: baddie

}

|> beat_up(hero.bracelets_of_submission)

|> interrogate(hero.lasso_of_truth)

|> hand_to_police()

{:ok, "I will fight for those who cannot fight for themselves"}

end

def fight_criminal(%Batman{} = hero, %GenericBaddie{} = baddie) do

%FightScene{

protagonist: hero,

antagonist: baddie

}

|> beat_up(hero.tools)

|> interrogate(hero.intimindation)

|> hand_to_police()

{:ok, "I am vengence"}

end

# ...

end

HeroAction.fight_criminal(batman, criminal)

The guarantee of this code is that you’re able to hand it anything that matches

the type of hero and baddie, and you will always get an {:ok, slogan} in

return. There are no other possible way this could fail; it’s a total function.

The heroes always win and they take every opportunity to say their slogan.

Additionally, if you’re using an ElixirLS-enabled editor, you can get some hints while developing:

Communicating with each other is an important part of developing software. Rarely is software developed by one and only one person, and even if developed solo, you have your future and past selves to communicate with. Documenting such typespecs assist you with creating total functions that let you compose functions safely. That leads us to our final pattern we’ll explore today.

Composition

Here’s the clencher, all the patterns we see above are repeated everywhere. When you have a big problem to solve with code, you approach it the same exact way as you would a small problem: with functions. You don’t have to shift paradigms in how to solve a problem depending on its scale.

Object-oriented programming has objects in the large, and methods in the small.

Functional programming has functions in the large, and functions in the small.

– Scott Wlaschin: Functional Programming Design Patterns

This is comforting, because when we already have a business problem we’re trying to solve, we don’t need a language problem or tooling problem clouding our judgment. Our brain can focus on one thing at a time and “zone out” on solving the business problem with our familiar and patterned toolset.

In gaming, it’s important to not frustrate the player with too much difficulty too soon. You have to give the player tools to solve the presented problems first. Once they’ve mastered the tools, then you can make them apply their newfound knowledge to the new problems. Likewise, we want Elixir (our tool) to not be one of the problems as we solve the main problem (the business). Otherwise they will give up and tell all their friends “this game sux.”

Understood

These patterns are pervasive in all Elixir codebases I’ve seen, and because those patterns are common, developers have a good way to communicate with each other which is the ultimate goal.

Nostalgia has a positive effect on the person. These patterns of our past remind us of who we used to be or some aspect of how we identify ourselves. Most importantly, nostalgia increases our sense of belonging and encourages growth.

The Theory of Fun explains that fun is the emotional response to learning; the reward for continuing to learn. What people learn are patterns in a variety of settings: school, childhood, adulthood, that one time at the bar where I talked too much, competitions, and (like we explored) video games. We often have fun when seeing patterns reoccur.

Software development is chock-full of patterns. Developers apply patterns constantly to problems they encounter when trying to build something. I focused on Elixir here, but this is true for many languages and frameworks; some maybe more true than others. Elixir has excellent patterns, and developers that share the same patterns understand each other, which is all we really want in the end anyway – to be understood.

I’ll leave you with a quote:

To [find good patterns] we must rely on feelings more than intellect.

To work our way towards a shared language once again, we must first learn how to discover patterns which are deep, and capable of generating life.

The specific patterns, out of which a building or a town is made, may be alive or dead. To the extent they are alive, they let our inner forces loose, and, set us free; but when they are dead they keep us locked in inner conflict.

– Christopher Alexandar (author of A Pattern Language)

Want to learn more about this topic? Check out these inspiring talks:

Special thanks to Quinn Wilton for proofreading!